“Do not ask where Hearts are

playing and then look at me askance. If it's football that you're wanting, you

must come with us to France!”

Private George Blaney, Castle

Brewery, Edinburgh, December 1914

Last week I attended Tynecastle for

the Hallowe’en fixture between Heart of Midlothian and their cross-city rivals

Hibernian. It was my first Edinburgh Derby since August 1989, which had been my

first ever Hearts live game. Since then I’ve watched the ‘Boys in Maroon’ in

such diverse places as Bologna, Prague, Madrid and, er, Falkirk. They are my

‘Scottish team’ and, thanks to the antics of the Allams, they have come pretty

close to usurping Hull City in my affections these past few years.

But why Hearts?

My affinity with The Jam Tarts

began back in the mid-Eighties, when the unfolding tale of their heart-breaking 1985/86 season resonated strongly with somebody still scarred by the

events of Turf Moor ’84. My involvement with the football fanzine movement then

helped move things on. Among the many

fanzines we struck up relationships with in those early days of Hull Hell & Happiness was Heartbeat, produced by a group of Hearts

supporters based in and around Manchester. What their A4-sized publication

lacked in quality of production it more than atoned for in quality of content;

especially its attacks on its bitter rivals in which the editors certainly

didn’t hold back. Many were not only very funny but bordered on tasteless. It

was the sort of thing we were wanting to do at HH&H prior to our summoning by The Don. As such, we quickly

adopted Heartbeat as our favourite

other fanzine. Editor Mike Van Vleck was a man with allegiances to various

sports teams and it was through his support of Salford Rugby League that I

finally made his acquaintance, courtesy of a game against Hull Kingston Rovers

in March 1989. A follow-up visit to see The Tigers entertain Hibs the following

pre-season cemented our friendship and a month later, I joined the Manchester

Hearts at a raucous Tynecastle where a goal from “the big Moose” was enough to

secure victory on a sodden summer afternoon.

Almost thirty years later, my

second derby experience would be remembered more for the accompanying

crowd-related incidents than for the quality of football on the pitch. But even

though the game itself was poor, the anticipation and atmosphere was something

I’ve not experienced at a City match for some time. Furthermore, as I wandered

around Edinburgh in the days before and after the game – as part of a half-term

mini-break with the family – it reinforced the affection I now have for my

adopted team and the city that spawned it. This weekend, when we mark the

centenary of the Armistice that ended the Great War, those bonds will be

strengthened even further. As I gather in Ypres to mark the eleventh hour of

the eleventh day of the eleventh month, along with many others uppermost in my

thoughts (my family ancestors and the ‘Easington Fallen’ who I travelled to

France and Flanders to honour last year) I will think of Heart of Midlothian

Football Club – “the team

that went to war for Britain”.

The

story of the involvement of Hearts FC in the First World War has been

brilliantly described in two books (Jack Alexander’s McCrae’s Battalion: The Story of the 16th Royal Scots (Mainstream, 2004) and Tom

Purdie’s Hearts At War 1914-1919 (Amberley, 2014)). It was

also the subject of a couple of fine newspaper articles, courtesy of Alex Massie in The Guardian from 2005 and The

Independent’s Robin Scott-Elliott four years ago in a piece

to mark the centenary of the start of the First World War. It is a tale guaranteed to stir the emotions, describing how “the

best team in Hearts’ history” turned their backs on footballing glory to go to

war.

At

the start of the 1914/15 season, Hearts were described as the “young

pretenders” of Scottish football but a 2-0 opening day win over champions

Celtic at Tynecastle underlined their title credentials. Six wins from their

opening six games had them sat proudly atop the league, a position they would

maintain for much of the campaign. By November the only points dropped in the

first fourteen games had come courtesy of a careless defeat at the hands of

Dumbarton and a surprise draw against Queens Park. They were looking

increasingly good for a first Scottish League title since 1896/97. Then the Great

War intervened. Having already seen army reservists Neil Moreland and George

Sinclair called-up at the outbreak of hostilities, winger James Speedie joined

them immediately after a 2-0 home win over Falkirk on 14 November, having

answered a half-time appeal made on behalf of the Queens Own Cameron

Highlanders. The Edinburgh Evening

Dispatch proudly proclaimed, “Three Hearts men with the Colours now”. That

number would soon increase dramatically.

As the

military crisis deepened in France, the pressure on young men to ‘volunteer’

became intolerable. Football became a target of “an orchestrated campaign of

abuse”[i], with satirical magazine Punch printing a cartoon urging men to

take part in the ‘Greater Game’ – played not for trophies but on the field of

battle. In Parliament, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith was urged to “introduce

legislation taking powers to suppress all professional football for the

continuance of the war”. As the “leaders of the Scottish League and considered

by many observers to be the most irresistible footballing combination in Great

Britain”, Hearts became a principal target. A letter from ‘The Soldier’s

Daughter’ in the Edinburgh Evening News

basically accused Hearts players of cowardice and suggested they adopt a nom de

plume of ‘The White Feathers of Midlothian’. It enraged those in the Tynecastle

dressing room. A few days later the popular local businessman and Liberal MP

Sir George McCrae asked manager John McCartney about the possibility of some of

the Hearts players joining the battalion being raised by him, “telling him that

such actions would make for a large following and a speedy formation of the

unit”. His request was granted and eleven players immediately signed-up, with five

others turned down on medical reasons. Among the few who didn’t join

immediately were brothers Archie and Jimmy Boyd, who first wanted to discuss

the matter with their mother. In the event “Young Jimmy made the decision for

them both. Archie was engaged to be married and had more to lose”.

Between

August and November 1914, sixteen Hearts players became ‘soldier footballers’ –

a figure unequalled in the United Kingdom and one that would almost double over

the next two seasons”[ii]. Among those enlisting

later was the captain, Bob Mercer who had originally been turned down due to a

torn knee ligament. Along with his team-mates he now “traded the playing fields

of Scotland for the killing fields of France (and) the roar of the crowd for

the roar of gunfire” By their actions, Heart of Midlothian FC became the first

British football team to sign up en masse. At the Hearts AGM of July 1915, it

was reported that “the lead established by these gallant youths reverberated through

the length of the land” and “some 600 supporters and shareholders followed suit

and joined up”. Many of these supporters enlisted in direct response to a Press

Statement released by the Hearts Board of Directors, in which they stated their

“earnest desire” that “an entire ‘Hearts Company’ be formed of players, ticket

holders and general followers”. The Statement read:

“Now then young men, as you have

followed the club through adverse and pleasant times, through sunshine and

rain, roll up in your hundreds for King and Country, for right and freedom.

Don’t let it be said that footballers are shirkers and cowards. As the club has

borne an honoured name on the football field, let it earn its spurs on the

field of battle.”

Those

answering the call were offered free admission to the Edinburgh Derby on

Saturday 5 December. “Eight hundred men duly turned up and marched into the

ground prior to kick-off” before “both teams emerged to thunderous applause”.

Conditions matched the reception but Hearts made light of them to “sweep

Hibernian back to Leith”. Tom Purdie said their play “lit up grey leaden skies

in a 3-1 win”.

Heart

of Midlothian were not alone in answering McCrae’s call. In total some 75 clubs

were represented in the 16th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Scots, otherwise

known as ‘McCrae’s Battalion’. These ranged from junior clubs to the likes of

Raith Rovers, Falkirk, Dunfermline and Hibernian. In addition there were representatives

of other sports, including rugby union, cricket, field hockey, swimming,

athletics and bodybuilding. The 16th Royal Scots was the original Sporting

Battalion and the first to earn the ‘Footballer’s Battalion’ sobriquet.

By

the start of 1915 the players’ military training had begun, involving long,

exhausting runs in the nearby Pentland Hills. The rigours eventually began to

take its toll, with bouts of influenza and blisters a recurring issue. Having

won 19 of their opening 21 games that season, playing football previously

described in the Press as "dainty, dazzling" and being "full of

pace and panache”, Hearts players (unlike those of either Celtic or Rangers) eventually

succumbed to the exertions of having to combine weekly military drills with

weekends playing football. They won only eight of their 17 games

post-mobilisation and when “a lacklustre Hearts team” were beaten 1-0 at St

Mirren on 17 April, Celtic “hurried past them” to eventually take the title by

4pts. An embittered Edinburgh Evening

News stated:

“Hearts have laboured under a

dreadful handicap, the like our friends in the west cannot imagine. Between

them the two leading Glasgow clubs have not sent a single prominent player to

the Army. There is only one football champion in Scotland and its colours are

maroon and khaki.”

Tom

Purdie describes how the Hearts players came off the Love Street pitch “totally

and utterly disconsolate, mentally and physically exhausted. They sat within

the changing room in numb silence”. Manager John McCartney addressed them and

expressed his utmost pride in their efforts before leaving the room to stand

alone in the corridor, where it was said he too had tears in his eyes. He knew in

his heart that some of those players he’d left in the changing room would never

play together in a maroon jersey again. McCartney later told the Edinburgh Evening News that his team had

played at times when they were so tired they could hardly stand. In addition, the

league’s top scorer Tom Gracie had been diagnosed with leukaemia but had asked

his manager to keep it from the other players. Yet despite all this, they had

taken things to the final day. He said, “Edinburgh is proud of them”. It’s

cruelly ironic that, similar to the season that first wooed me to the club, finishing

second didn’t deprive the Hearts players of the glory their efforts deserved.

However, in this particular case, “they had (also) won the hearts and

admiration of the nation”.

On

the morning of 18 May 1915, McCrae’s Battalion went to war. Purdie wrote:

“1,100 men marched proudly down the Mound and Market Street to Waverley Station

to the sound of the pipes and drums. Thousands turned out to wish them a fond

farewell and a safe return”. But what must have seemed at the time like a

‘glorious adventure’ descended into anything but. In total, seven first team

players failed to return. James Speedie was the first to fall, killed in action

at the Battle of Loos on 25 September, just eleven weeks after arriving in

France. A month later Tom Gracie succumbed to his illness. Duncan Currie,

Ernest Ellis and Harry Wattie fell on the first day of The Somme, to be

followed later by John Allan and the aforementioned Jimmy Boyd who also gave their

lives before hostilities were ended. Several more sustained injuries that

ensured they would never play football again. A detailed list of those killed

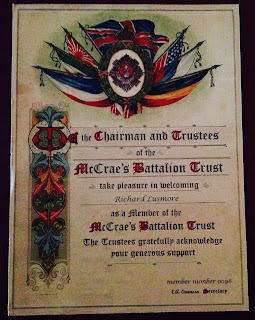

and wounded is available on the excellent McCrae’s Battalion Trust website but suffice to say

no other football club in this country paid such a price – on or off the field.

Hearts continued to function as a team during the War years, largely helped by servicemen home on leave or those players involved in vital war work at home. Amid falling attendances, struggling finances, ongoing team disruption and continuing bad news from the Western Front the Scottish League somehow carried on. Hearts managed a creditable fifth-place finish in 1915/16 but that proved their best. Mid-table placings followed over the next three years. Five days after the Armistice in November 1918, The Jam Tarts produced their best display of the season to beat Third Lanark 5-0 at Tynecastle in front of a 7,000 crowd, many who joined in the singing of patriotic songs, led by the Grassmarket Band. As Purdie writes, “There was a special welcome back to Tynecastle for some brave individuals”. Honouring a promise made at the time of their departure, “a Main Stand season ticket was given to the returning members of 16 Royal Scots C Company who had been season ticket holders, shareholders, officials or indeed players”. On the reverse of the ticket, along with the Royal Scots crest and the person’s name, rank and service number, was printed the following:

Hearts continued to function as a team during the War years, largely helped by servicemen home on leave or those players involved in vital war work at home. Amid falling attendances, struggling finances, ongoing team disruption and continuing bad news from the Western Front the Scottish League somehow carried on. Hearts managed a creditable fifth-place finish in 1915/16 but that proved their best. Mid-table placings followed over the next three years. Five days after the Armistice in November 1918, The Jam Tarts produced their best display of the season to beat Third Lanark 5-0 at Tynecastle in front of a 7,000 crowd, many who joined in the singing of patriotic songs, led by the Grassmarket Band. As Purdie writes, “There was a special welcome back to Tynecastle for some brave individuals”. Honouring a promise made at the time of their departure, “a Main Stand season ticket was given to the returning members of 16 Royal Scots C Company who had been season ticket holders, shareholders, officials or indeed players”. On the reverse of the ticket, along with the Royal Scots crest and the person’s name, rank and service number, was printed the following:

“Voluntarily these men went forth

to fight for King and Country. The gloomiest hour in the nation’s history found

them ready. As pioneers in the formation of a brilliant regiment, sportsmen the

world over will ever remember them. Duty well done they are welcomed back to

Tynecastle; Hearts of Oak!”

To

mark the end of the fighting, it was announced that a Victory Cup would be

competed for in 1919 (the Scottish Cup having been suspended for the duration

of hostilities). Eighteen teams were entered and it was widely agreed that a

Hearts victory would not only have been “pleasing” but “fitting”. In the event,

they again came up just short. A bye in the first round was followed by away

wins at Third Lanark and Partick Thistle, before Airdrieonians were subjected

to what Purdie terms “a devastating display of football” in a 7-1 scoreline in

the semi-final at Tynecastle. The final saw Hearts face St Mirren in front of

60,000 at Celtic Park on 26 April 1919. Purdie writes: “Outwith the ‘Saints’

fans, this was a game that probably the whole of Scotland wanted Hearts to win

due to the sacrifices they had made during the war years”. Three extra-time

goals for The Buddies ensured it was not to be. Hearts were runners-up. Again.

It’s

widely acknowledged that had the Great War not come along, the Hearts side of

that era “might have established a dynasty in Edinburgh”, leading to Scottish

football being “carved up between three rather than two powers”. In his 2005

piece, Massie went so far as to suggest that the Kaiser can perhaps be blamed

for the lack of competitiveness in the Scottish game! As it is, since the Great

War Hearts have largely remained also-rans, which is possibly another reason I

– as a Hull City supporter – was drawn to them in the first place!

Sadly,

I believe the story of the Hearts ‘soldier footballers’ is one that still

remains largely unknown to most football supporters. Indeed, had I not been

drawn to Hearts by that 1985/86 season, it may have been one that I too would

have easily overlooked? There have been attempts to address this. In November

2014 BBC Learning produced Footballers United as part of its World War

One season and more recently, A War Of Two Halves is enjoying a second run

at Tynecastle having proved a big hit at the Edinburgh Fringe. Sadly, my visit was

a week too early for the latter but simply sauntering around the streets of ‘Auld

Reekie’ brought the words of Alexander and Purdie to life; from the recently

re-named McCrae Place, and Castle Street in the

New Town to the Haymarket Memorial and Tynecastle itself. Walking

along Princes Street I allowed myself to imagine the gridlock as huge crowds of

well-wishers gathered to provide the brave Hearts lads with a magnificent

send-off. I even looked up at the Castle and imagined the “weather-beaten

fortress nodding its head in approval”. Many a passing tourist – and local for

that matter – must’ve wondered who this Sassenach was wandering around with a

fixed smile on his face, seemingly staring into space. But before I got too

carried away on a wave of nostalgia, I was away to Ryries for a pre-Derby

livener or three… (As an aside, a bus ride along Easter Road to Leith in order

to visit the former HMY Britannia had me chuckling as I imagined that 1914 Hibs

team being “swept back” along the very same route over a hundred years earlier)

The

Hibees certainly weren’t swept away in my latest Edinburgh Derby, the game

finishing goalless with the visitors surviving a second half sending-off and a

late disallowed goal. It was a game played in a tetchy atmosphere far removed

from that described by Purdie, with Hearts keeper Zdeněk Zlámal and Hibs boss

Neil Lennon both going to ground after separate spectator-related incidents.

These incidents provoked far more post-match talking points than the game

itself. The Edinburgh Evening News back

page led with the headline “You Coward”. Despite the dropped points and a

subsequent weekend defeat by Celtic, Hearts arrived in November sitting above

the Glasgow side at the top of the league, just as they had done in November

1914 – when the term “Coward” had a far more sinister connotation and the ‘Boys

In Maroon’ really were the ‘Talk o’ the Toon’.

Lest

we forget.

FOOTNOTE:

My

previous blog posts around the subject of the Great War commemorations are as

follows: A Greater Game (24/11/2014); Oppy Wood, Hull Pals & finding

Easington’s Fallen

(09/11/2017)

[i]

From http://www.mccraesbattaliontrust.org.uk/white-feathers-of-idlothian/

[ii]

From http://www.mccraesbattaliontrust.org.uk/the-sporting-battalion/